All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Synaptic Signals from Glutamate-Treated Neurons Induce Aberrant Post-Synaptic Signals in Untreated Neuronal Networks

Abstract

Background and Objective:

Glutamate neurotoxicity is associated with a wide range of disorders and can impair synaptic function. Failure to clear extracellular glutamate fosters additional cycles and spread of regional hyperexcitation.

Methods and Results:

Using cultured murine cortical neurons, herein it is demonstrated that synaptic signals generated by cultures undergoing glutamate-induced hyperactivity can invoke similar effects in other cultures not exposed to elevated glutamate.

Conclusion:

Since sequential synaptic connectivity can encompass extensive cortical regions, this study presents a potential additional contributor to the spread of damage resulting from glutamate excitotoxicity and should be considered in attempts to mitigate neurodegeneration.

1. INTRODUCTON

Glutamate is the brain's most abundant neurotransmitter and its regulation is critical [1]. Neuronal dysfunction and degeneration induced by excessive glutamate is characteristically linked with acute conditions, such as ischemia and traumatic brain injury [2]. However, glutamate excitotoxicity has also been linked to chronic neurodegenerative disorders, including amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, multiple sclerosis, Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson's disease [3-6]. A critical increase in extracellular glutamate can impair synaptic plasticity and long-term potentiation [7], which may underlie the relationship of glutamate toxicity to this wide range of neurodegenerative conditions.

Neuroprotective measures for glutamate excitotoxicity are lacking [3, 4]. Glutamate transporters may play a role in mitigating glutamate excitotoxicity since reduced glutamate transporter expression is observed in neurodegenerative diseases [1, 7].

Glutamate-induced hyperexcitation has been studied extensively in cortical culture [8-10]. These have modeled primary, secondary, tertiary, and quaternary phases of injury and provide the potential for the development of interventions for each of these phases [8]. Reductionist studies in culture have demonstrated that glutamate toxicity induces aberrant kinase activation and can disrupt the balance of other neurotransmitters [9, 10]. Herein, the impact of glutamate on synaptic signaling in cortical cultures was monitored and it was demonstrated that aberrant signaling resulting from glutamate toxicity can spread synaptically to neurons not exposed to elevated glutamate.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

Primary murine embryonic cortical neurons harvested at day 17 of gestation from C57BL/6 mice were plated at ≥100 cells/mm2 on poly-d-lysine/fibronectin-coated, Multi-Electrode Arrays MEAs; Multichannel Systems, Reutlingen, Germany) in B27-supplemented Neurobasal medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), as described in previous studies [11, 12]. The sacrifice of the pregnant female was according to procedures approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (protocol number 13-03-02-She). In efforts to achieve a natural environment relative to in situ conditions, the chamber surface was coated with a 50-50% mixture of poly-L-lysine/fibronectin, and no efforts were made to eliminate glial cells. In this regard, glial cells both contribute to synaptic development [11, 13] and are involved in secondary damage in traumatic brain injury [14]. Synaptic signals are routinely detected as soon as a network of neurites is visible (≤ 2 weeks). Still, cultures are maintained for 1 month prior to experimentation to allow for full development and stabilization of the neuronal network [11, 15].

Mature networks were treated for 20 min with 5mM glutamate. Glutamate treatment was previously confirmed to invoke calcium influx in these cortical cultures [9].

MEAs were placed in a MEA-1060-INV amplifier (Multichannel) and synaptic activity was recorded prior to and following the addition of glutamate via a DT9814 data acquisition system (Data Translation; Marlborough, MA). Prior studies using combinations of excitatory and inhibitory neuronal antagonists have confirmed the synaptic origin of signals [11]. Additional mature networks not treated with glutamate were stimulated with signals recorded from other networks during glutamate treatment. As in the prior studies involving stimulation of networks with digitized synaptic signals, recorded signals were applied at a singular MEA channel with an adjacent electrode utilized as a ground; this localized signaling loop restricted the spread of the signal among synaptically connected clusters of neurons [11, 12, 15]. Signal frequency and amplitude were monitored via software (“Raptor”) developed in the laboratory (freely available on request) with export to Microsoft Excel [12, 15], where signals ≥1mV deviation from baseline were quantified.

3. RESULTS

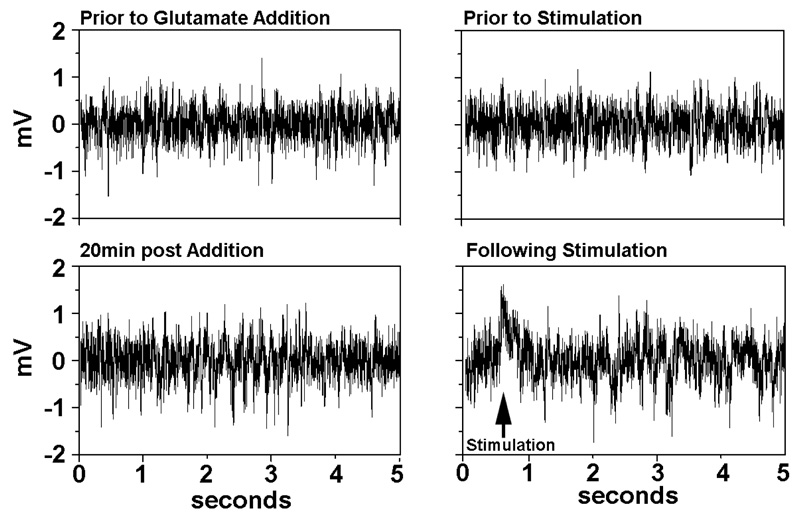

Treatment of cortical networks for 20min glutamate increased high-amplitude (≥1mV) signals by 2.4-fold, indicating induction of hyperactivity (Fig. (1) left panels). The additional networks, not treated with glutamate, were stimulated next with a 5sec segment of a signal recorded from a glutamate-treated network, which immediately fostered a 1.8-fold increase in high-amplitude signals (Fig. (1) right panels); signal patterns returned to normal 30min following stimulation (not shown). The impact of stimulation with this signal glutamate signal contrasts with the prior studies in which stimulation with a segment of a synaptic signal from a healthy culture induced synchronous waves of low-amplitude and organized bursts, rather than high-amplitude signals [11, 12, 15].

4. DISCUSSION

Glutamate neurotoxicity is associated with a wide range of disorders and even in the absence of overt disorders, it can impair synaptic function [3-7]. Failure to clear extracellular glutamate fosters additional cycles and spread of regional hyperexcitation [1, 2, 7, 16]. The present findings in the ex vivo neuronal networks suggest that regional glutamate-induced hyperactivity can also invoke hyperactivity in synaptically connected neurons in cortical regions distal from an area exposed to elevated extracellular glutamate. Since sequential synaptic connectivity can encompass extensive cortical regions, the synaptic transmission of aberrant signaling presents a potential additional contributor to the spread of damage, resulting from glutamate excitotoxicity and should be considered in attempts to mitigate neurodegeneration. Monitoring signaling provides an opportunity to detect what may be the earliest signs of trauma, before any serious consequences that will result from extensive calcium influx; resumption of normal signaling within 30 min of a single stimulation with a synaptic signal from a network undergoing glutamate excitotoxicity supports this line of reasoning.

CONCLUSION

Glutamate toxicity can also be induced by elevated homocysteine, which itself can arise from genetic and/or dietary deficiency, leading to aberrant kinase activation, cytoskeletal compromise, DNA damage, and neuronal apoptosis [9]. Underlying genetic or dietary deficiency could, therefore, potentiate the extent of damage caused by glutamate following a traumatic injury.

Cell culture analyses also demonstrated alterations in GABA-mediated signaling following stretch injury, apparently mediated by kinase hyperactivation [10]. This may result from glutamate toxicity since glutamate activates this kinase [17-19]. Future directions to assess the full extent of glutamate toxicity should include examinations of multiple additional neurotransmitters and kinases.

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

The sacrifice of the pregnant female was according to procedures approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (protocol number 13-03-02-She).

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

Not applicable.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Not applicable

AVAILABILITY OF MATERIALS

The software program used to record and quantify signals “Raptor,” designed in this laboratory, is freely available to all investigators upon request.

Data obtained with this program, and used in this manuscript, is available upon request.

FUNDING

This work was supported by the U.S. Army Research Office, contract number W911NF-06-C-0094 and W911NF-08-1-0222.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest, financial or otherwise.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful for the continued advice of Dr. Elmar Schmeisser.